Child Pays for Parent: Part 3

Jun 9, 2019Eliminating O(n^2) processing for unconfirmed transaction chains and permitting longer chains

Background

Two previous essays were written on this topic, but ultimately the ideas and methodology were abandoned due to problems and edges cases discovered while attempting to implement those methods. The first section, of the first essay is republished here for background.

Bitcoin ABC inherited a feature from Bitcoin Core called “Child Pays For Parent” (CPFP). The purpose of this feature is to allow transactions which spend outputs from other transactions, which are currently in the mempool, to pay fees on behalf of the ancestor (e.g. parent) transactions. This is useful in the case where the parent would not be included in the next block, and someone desires to spend it’s output immediately. From a mining perspective, it would be more profitable to include the pair of transactions, receiving both their fees, than include some entirely different transaction.

While this seems like a useful feature, it causes several scaling issues. When constructing a new block, the software needs to know which transactions to include in the block – but it is no longer based solely on individual transaction fees, but instead on transaction fees of each chain of transactions (herein called a package).

As new transactions in a package come in, we must look up all their parents, and update the ancestors. This means, for a package of size N, we must do this ~N^2 Times:

bool CTxMemPool::addUnchecked(...) {

...

const CTransaction &tx = newit->GetTx();

std::set<uint256> setParentTransactions;

for (const CTxIn &in : tx.vin) {

mapNextTx.insert(std::make_pair(&in.prevout, &tx));

setParentTransactions.insert(in.prevout.GetTxId());

}

...

// Update ancestors with information about this tx

for (const uint256 &phash : setParentTransactions) {

txiter pit = mapTx.find(phash);

if (pit != mapTx.end()) {

UpdateParent(newit, pit, true);

}

}

UpdateAncestorsOf(true, newit, setAncestors);

UpdateEntryForAncestors(newit, setAncestors);

...

}

Additionally, when a new block is found, its transactions must be removed from the mempool. In this case, this extra accounting must be updated again. In order to ensure that chains are not broken up while updating the accounting, this needs to be done in topological order. Since the introduction of CTOR, blocks are no longer in topological order, so they must be first sorted. Topological sorting is linear time in the number of nodes and edges(approximately linear in terms of block size). Once we have topologically ordered them, we must then update each descendant’s accounting. This is again N^2 Time:

void CTxMemPool::removeForBlock(...) {

...

for (const CTransactionRef &tx : reverse_iterate(disconnectpool.GetQueuedTx().get<insertion_order>())) {

...

setEntries setDescendants;

CalculateDescendants(tx, setDescendants);

for (txiter dit : setDescendants) {

mapTx.modify(dit, update_ancestor_state(...));

}

...

removeUnchecked(tx);

}

...

}

Since the algorithms require O(n^2) computation, it is vulnerable to DoS attacks. Therefore, a limit was added in order to prevent chains of lengths greater than 25 (by default) from being accepted by the node. The following code was added to enforce this rule:

static bool AcceptToMemoryPoolWorker(...) {

...

if (!pool.CalculateMemPoolAncestors(

entry, setAncestors, nLimitAncestors, nLimitAncestorSize,

nLimitDescendants, nLimitDescendantSize, errString)) {

return state.DoS(0, false, REJECT_NONSTANDARD,

"too-long-mempool-chain", false, errString);

}

...

}

While this feature appears useful, it creates a couple of problems:

- It adds n^2 complexity to accepting new chained transactions.

- It adds n^2 complexity to processing (not validating) a new block.

- It prevents long chains of zero-conf transactions in order to prevent DoS attacks.

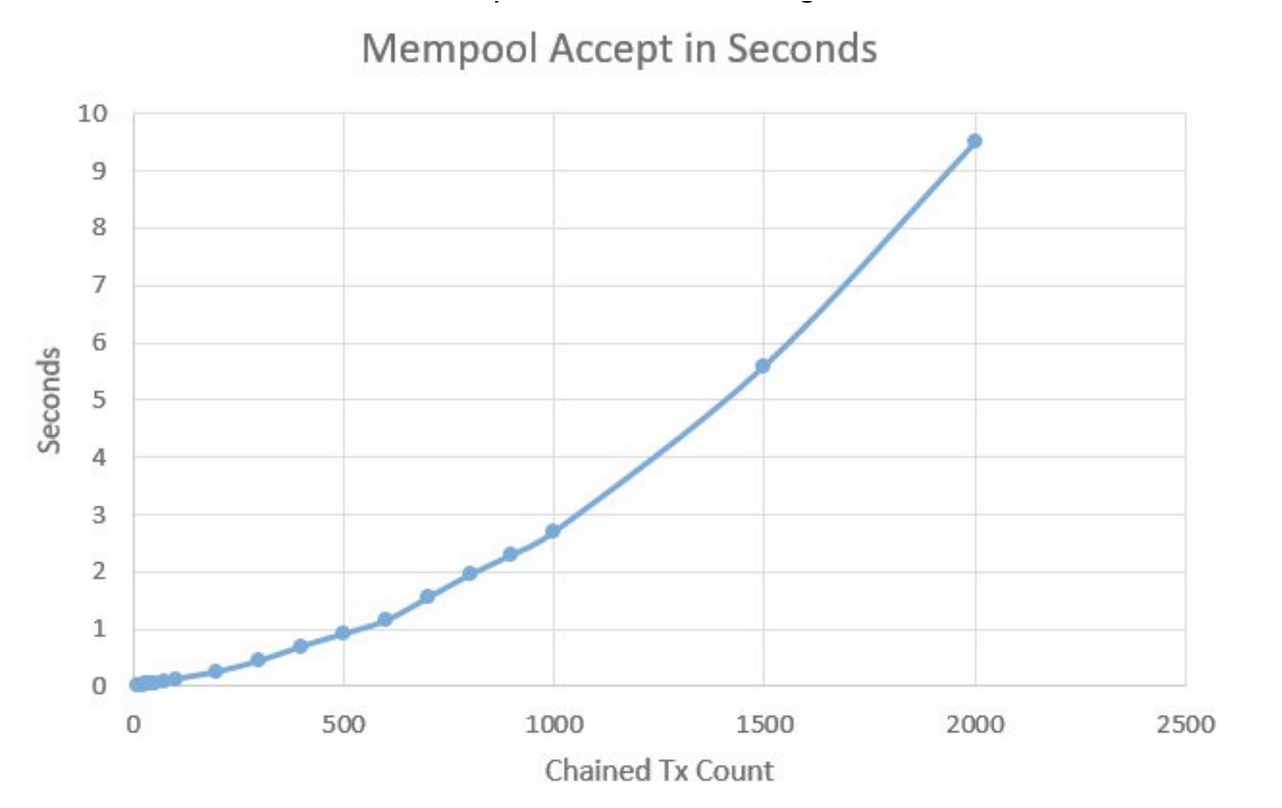

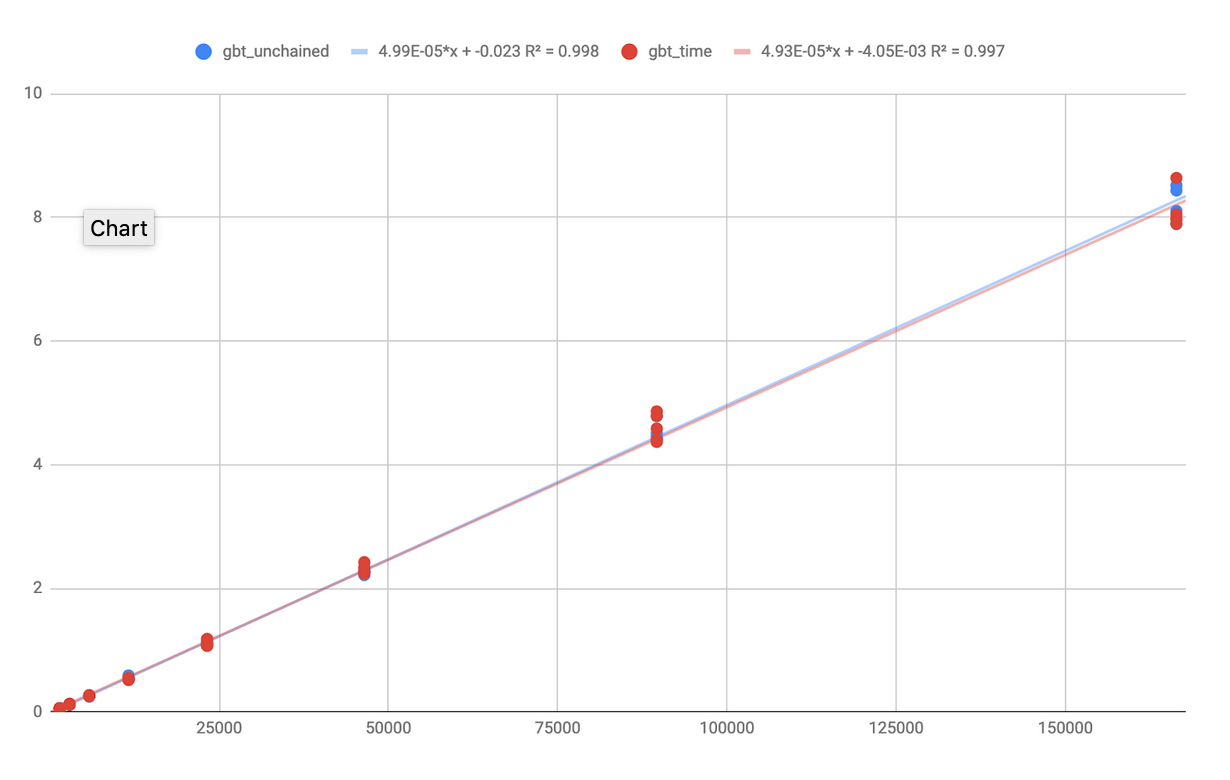

(Fig 1) Taken from Raising the Ancestor and Descendant Transaction Limit for Bitcoin Cash

(Fig 1) Taken from Raising the Ancestor and Descendant Transaction Limit for Bitcoin Cash

Despite the time complexity of this feature, child pays for parent is useful in several circumstances:

- Sustained usage which exceeds demand for blockspace.

- Attempts to DDoS Bitcoin by sending lots of transactions with small fees, and a legitimate user would like to prioritize a transaction.

- A transaction sent has a fee which is relayable, but falls below miners configured threshold.

The first case is avoided in Bitcoin Cash due to user experience considerations.

For the second case, we have not observed that this occurs for any significant length of time. It is actually quite costly to carry out such an attack, and gains the perpetrator nearly nothing. At most, we need to ensure that we have some quality of service mechanism in place.

In the final case, where the minimum relay fee is less than the minimum block fee, a receiving user may want to spend out of the mempool and ensure that both transactions will be confirmed.

Requirements:

- Enable removing the restriction of 25 transactions to a chain

- ~ Ensure processing chained transactions is <O(nlogn) for N in the chain length.

High Level Solution

The proposed solution to this problem is a multistage process:

- Separate block template transaction selection criteria from the mempool entirely.

- Use a fast heuristic to calculate package fees and support the majority of CPFP use cases, ensuring that the majority of existing tests pass.

- Remove the package fee calculation from the mempool acceptance procedure.

- Remove the 25-tx chain limit.

Package Fee Algorithm

For Code See: https://reviews.bitcoinabc.org/D2866

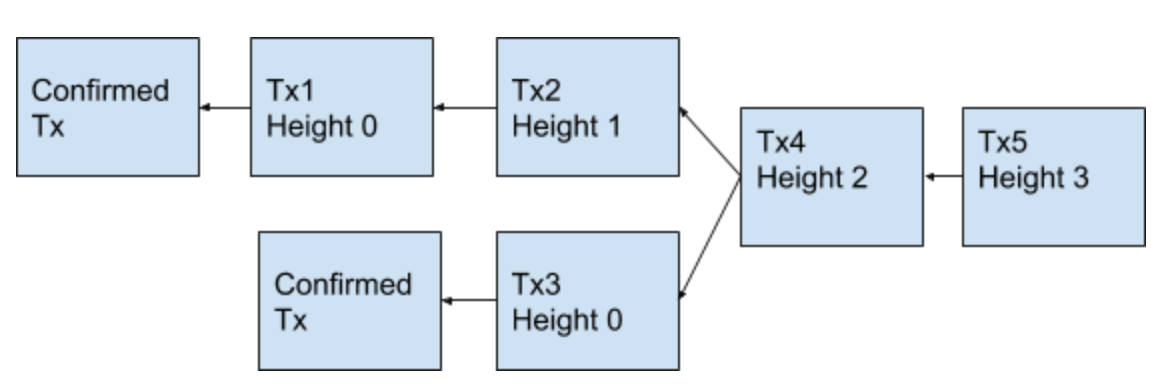

In order to remove these computational expenses, we switch to a simple model. During block candidate construction each transaction is assigned a height equal to the number of levels of transactions (See Fig 2) that will need to go into a block before it would be a valid inclusion (due to ancestors). Additionally, the height of a transaction which have higher package fee-rates than the maximum of their parent maximum packageFees parents are reset to height=0.

Each transaction is processed in sort order, where the sort is based on the “height”, and within the height based on its packageFeeRate (if it is height zero) or its feerate if it is non-zero. The result is that the complexity is O(nlogn) for the sort, and O(n+m) calculating the package information (where M is the number of edges in the transaction graph for). This is significantly lower complexity than the existing algorithm while allowing some rudimentary CPFP functionality.

Examples:

Example Transaction Chain

Example Transaction Chain

Without any package having package fees greater than a parent, the above set of heights for transactions would be produced.

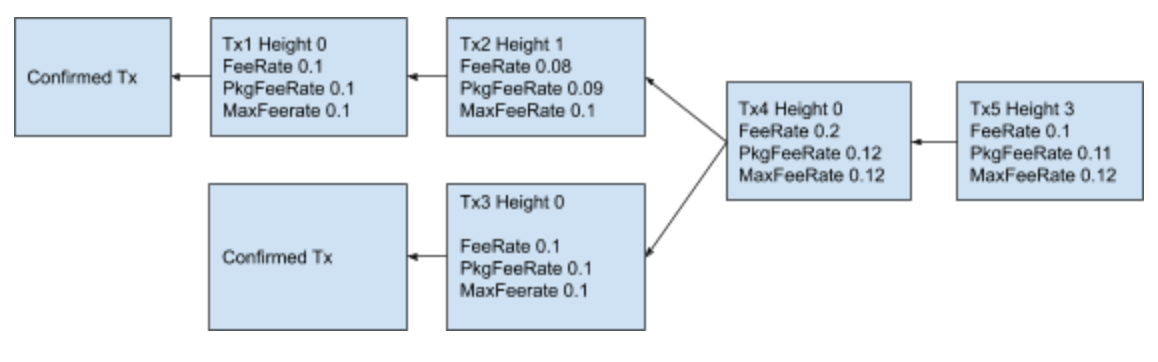

From the fee information, for each transaction, Tx4 is given a height of 0. When sorting the resulting list of transactions by height, and then by PkgFeeRate, the following total order will arise: Tx1, Tx3, Tx4, Tx2, Tx5. In upgrading Tx4 to height 0, we know we will not be doing worse by including it before Tx2. It may be the case that some of its ancestors sort before it, but that is okay. What is important, is that when we get to Tx4, we also include Tx2 while ensuring we are not doing significantly worse than including some other transaction. This property is guaranteed by this topology.

Example Transaction Chain with values from Algorithm

Example Transaction Chain with values from Algorithm

Rationale

As long as the mempool calculations are intertwined with logic for producing block templates, any change to the mempool code must include changes to the block template generation code. It is better, and less error prone, to make changes to one piece of a larger refactor at a time. For a progressive change, there are two possible options: Add additional calculations to the mempool which are faster than the existing algorithm, and then change the mining code to use them. Change the mining code not to depend on the mempool, and then remove the existing calculations from the mempool completely. However, the mempool fee calculations are complex, and each value requires updating when: new transactions are received, new blocks are received, transactions are dropped from the mempool, and when transactions are manually reprioritized. For the case when a new block is received, this must happen before a block validation can complete so that the mempool is in a consistent state for new transactions and mining. However, the block receipt operation degenerates into a bulk operation which is different code from iterative updates. This requires the same calculations to be made two different ways; leading to the potential for bugs if these calculations need to be changed in the future.

Due to the complexity, and computational expense, of maintaining mempool consistency during transaction acceptance, going with option 2 is proposed. There are some tradeoffs with moving package handling to the block template creation process.

GetNewBlock is called on a duty cycle by mining pool software. As long as it does take the cs_main, and mempool, locks for an extended period of time, moving the calculation to GetNewBlock does not hurt mempool acceptance in a significant way. Additionally, if GetNewBlock takes some additional time to work, this impacts mining performance immediately after receipt of a new chain tip. Additionally, some transactions may not confirm as quickly as they otherwise would had the template been updated sooner.

These tradeoffs are acceptable if we can reduce the total time spent in GetNewBlock with an improved package selection algorithm. The current version of addPackageTxns also recomputes package fees progressively as groups of transactions are added to the potential block. Since our proposed algorithm algorithm does not need to update fees progressively, we are able to realize significant time savings here. The proposed algorithm is O(|N|+|M|) where N and M are the number of transactions and edges in the mempool. Each transaction, and transaction dependency (edge), requires blockspace in a roughly linear fashion, ensuring the calculations scale roughly linearly with fees.

Additionally, decoupling the mempool from the mining code allows for the number of invariants the mempool has to enforce to be reduced. Instead of requiring that all package information must be consistent at the mempool boundaries, we now only require that the mempool not include any orphan transactions. With a single responsibility, large amounts of code can be removed from the mempool.

Studies in software defects show us that the ratio of bugs per line of code is roughly 20 bugs per KLOC. Given that Bitcoin ABC is mission critical software, choosing solutions which simply the overall codebase is wise. The total addition caused by these changes to miner.cpp is ~300 lines, while ~400 lines are able to be deleted. Additionally, one index and another 25 lines of code are able to be deleted from txmempool.cpp. Another 121 lines of unit tests may deleted in txmempool_tests.cpp. Step 3 of the proposed solution will likely remove approximately 500 more lines from the mempool.

Benchmarks

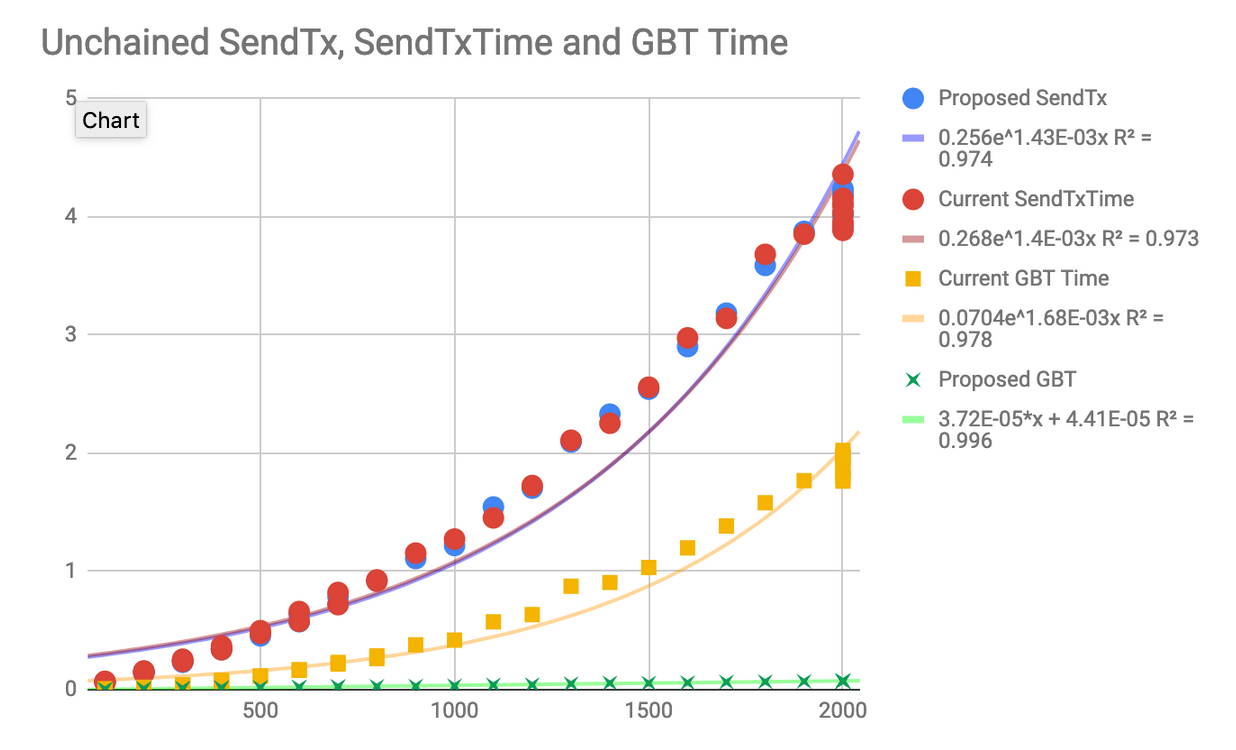

Benchmarks of altered vs unaltered code for transaction chains

Benchmarks of altered vs unaltered code for transaction chains

Figure (4) was generated using a modified test from David Froderick. Additional modifications were made to allow the chain length to be configured by command line, and so that the test would append a JSON entry to an output file. This was then run in a loop via a shell script for the above chain lengths. This was done for both a binary generated from D2866 and one from Bitcoin ABC master commit f5873a89b69437985a10fa997214ebf4adbb1fa0. As is clearly visible, the new getblocktemplate code scales very well with chain length. Additionally, the implementation is extremely naive with lots of room for optimization by removing hash table lookups, and improving locality for better cache hit rates.

Additionally, benchmarks were conducted vs the unmodified mining code for blocks of various sizes and for transactions with no descendants. The data is visualized in Fig(3). The x axis is the number of transactions. These were either 1 Input 2 output, or 1 input 1 output transactions of ~200 bytes on average. The overall performance is roughly linear for both algorithms. The difference between the algorithms is negligible.

Benchmarks of altered vs unaltered code for normal use

Benchmarks of altered vs unaltered code for normal use

Path Forward

The next step after include of D2866, is to remove and optimize package tracking code in the mempool. This is primarily deleting code which no longer has any dependencies.

After code removal is completed, if more progressive algorithms are still required, another component can be introduced which maintains block templates. It can run in a background thread, and maintain a block template based on messages passed to it from the mempool. For example, these events could be:

- Transaction added: Update the block template with this transaction, and reorder where needed, or drop the transaction from inclusion entirely.

- Transaction removed: Remove the transaction, and its descendants, from the template if found, and removal is desired.

- New block received:

- Clear the existing block template

- Bulk copy the remnants of the mempool

- Recalculate inclusions

Having such a component is also desirable in the future, as it can maintain transactions sets associated with WorkIds as per the BIP22 specification. Support for WorkIds will become necessary as block sizes grow. Passing around entire transaction sets to and from the node will become infeasible as block sizes grow.

Other Possible Solutions

Do fee calculation when entering the mempool then take a snapshot of the mempool when producing a block template

One option that was considered was to, as is currently done, calculate the fees for a transaction as they enter the mempool, and simply snapshot the transactions when creating a block template. However, the node must support producing blocks during times of sustained high use where the mempool size can be greater than the current block size. Therefore, this solution has some drawbacks:

- Fee calculation is limited to streamable algorithms.

- Block validation requires updating any transactions which are not cleared from the mempool before more blocks can be mined.

With respect to the first, calculating transaction fees upon admission to the mempool, the solution to fee calculation must be streamable. This means that other, possibly more efficient, solutions that only operate on completed sets are off-limits.

The second problem also poses more of a problem during conditions where sustained high use is occuring. If the block size is greater than the mempool size, receipt of a new block should clear the mempool. However, in situations where this is not the case, the remaining transactions must have their information updated. This must happen before a block has completed validating, and degenerates into bulk operation which is different from the iterative updates that are made for single transaction admittance. This requires the same calculations to be made two different ways; leading to the potential for bugs if these calculations need to be updated.

Additionally, tying the fee calculation logic to the mempool means that non-mining nodes must also perform these calculations wasting resources.

Conclusion

By decoupling the mempool from block creation we enabled a significant reduction in code complexity both of mining, and of the mempool. Mining pool operators are more easily able to customize block template production in the future. The chained transaction limit can be lifted or extended significantly, allowing for new use cases, and simplifying UTXO management for wallets driving complex Bitcoin Cash applications. Finally, with malleability fixes coming in November, chained transactions will not be vulnerable to malleability attacks. These two factors combined open up the possibility for applications which need to generate transactions at a high frequency without complicated UTXO management.